Ruth Hancock, Bo Hu, Raphael Wittenberg, Derek King, Marcello Morciano on behalf of the CASPeR team

Social care is important to older people who need help and support in their daily lives. Social care in England is currently not free of charge. Eligibility for publicly funded social care is subject to an assessment of care needs and a means test of savings and incomes. Adults who are not eligible for public support have to fund their own care. Those who are eligible for some public support typically have to make a contribution to the cost of their care. Changes are being introduced from October 2023 which will place a ceiling (or ‘cap’) on the amount that any individual has to spend over their lifetime on their care. There will also be changes to the ‘capital limits’ within the means test which will mean that some people who are currently not able to get publicly-funded social care because their savings (which for residential care, may include the value of their home) are too high, will be eligible for some help from their Local Authority with the costs of meeting their care needs even before they reach the cap.

In this study, we analysed the costs to the Government of these reforms, in the short and longer term, and compared the benefits for different groups of older social care users for example, care home residents compared with home care users, those on lower and higher incomes, those who are home-owners and those who are not. We focus on people aged 65 and over although the reforms will also affect younger adults. Our study drew on data published by the Office for National Statistics and NHS Digital and collected in national surveys such as the Family Resources Survey and the Health Survey for England. The findings do not take account of the effect of Covid-19 on the care sector or the economy more generally. (The short-term effects of Covid-19 are not yet reflected in our data and the long-term effects remain uncertain).

We estimate that total expenditure on long-term care for older people in England amounted to about £20 billion in 2018 at 2018 prices. Just under half of this cost was met by users themselves and the rest (£10.5 billion) was met from public funds, mainly from Local Authority (LA) budgets. In 2018, over half of LA spending on long-term care for older people went to people who were single and were not homeowners; just under 40% of spending went to older people in the lowest fifth of the income distribution.

We project that under the current funding system, public spending on long-term care for older people would need to nearly double between 2018 and 2038 to keep pace with the growing numbers of older people.

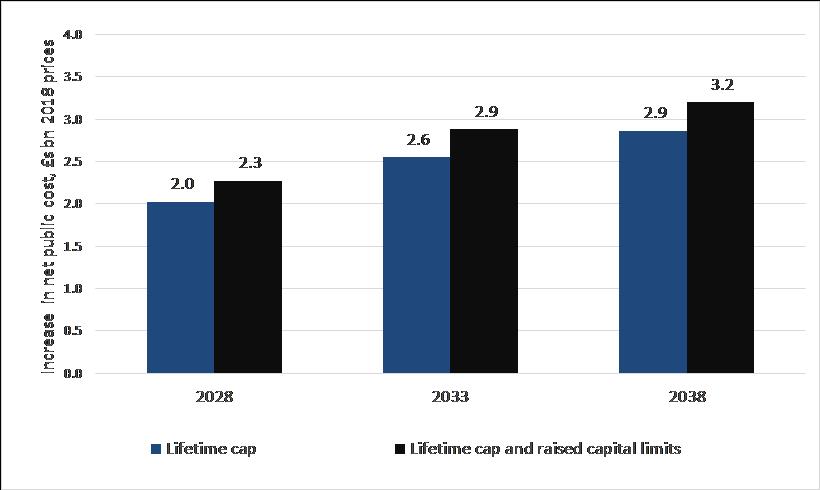

Under the reforms, we project public spending on long-term care for older people to be £2.3 billion higher in 2028 and £3.2 billion higher in 2038 (in 2018 prices) than if the current funding system continued (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Projected increases from the funding reforms in net public cost of long-term care for older people, England 2028-2038

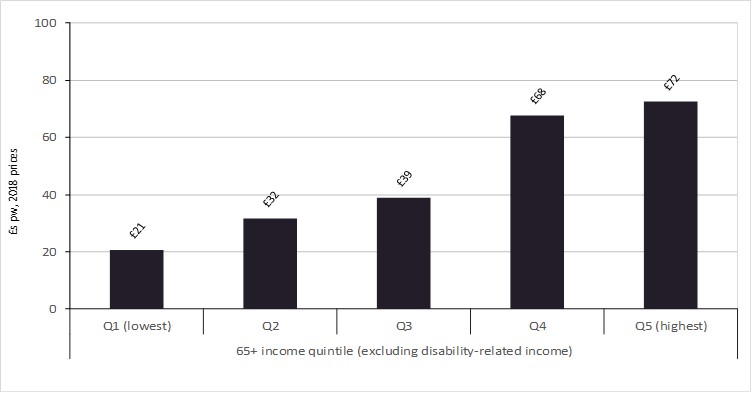

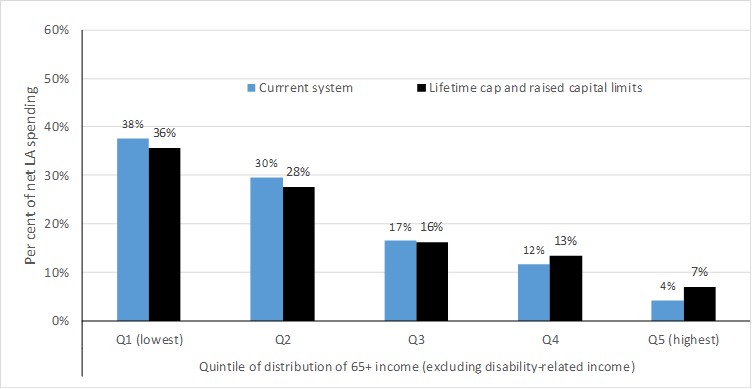

The nature of the reforms means that their financial benefits will be felt most by those who would pay substantial amounts towards their care under the current funding system. We project that care home residents stand to gain on average about £60 per week in 2028 (in 2018 prices) compared with £20 for home care users. The average gain in 2028 for homeowners is projected to be £64 per week in contrast to just £5 per week for people who do not own their homes. Gains will also be concentrated on older people on higher incomes (who also tend to have higher savings and housing wealth than older people on lower incomes). The average gain from the reforms for older people in the highest fifth (quintile) of the income distribution is projected to be £72 per week in 2028 compared with £21 per week for those in the lowest fifth of the distribution (Figure 2). Even so, public spending on long-term care for older people will remain concentrated on those on lower incomes (Figure 3).

Figure 2: Average gains in 2028 from charging reforms amongst care users aged 65+, £s per week, 2018 prices

Figure 3: Distribution of Local Authority expenditure on long-term care for people aged 65+, minus user charges, by income level

With no allowance for the effects of Covid or other recent economic developments, we project that the long-term care funding reforms due to be implemented in October 2023 will add about 15% to public spending on long-term care for older people by 2038. The reforms will reduce the amounts people have to pay towards their care from their own pockets. The main beneficiaries from these reductions will be people who would be required to pay substantial amounts towards their care under the current system such as single care home residents who own(ed) their own homes and those on higher incomes. Nonetheless, public spending on long-term care for older people will remain concentrated on those on lower incomes. Moreover, it is important to consider – as we do here – the whole package of reforms including the raising of the capital limits in the means test and the lifetime cap on care costs.

Ruth Hancock, R.M.Hancock@lse.ac.uk